By Don Jacobson

Most blues and rhythm and blues songs prior to the 1970s – when Curtis Mayfield, Marvin Gaye and James Brown pioneered a socially conscious black music – rarely had any topical references in them. Thus, references to Chicago in early R&B and soul music, even from records made in the city (and there were tens of thousands of them) are not commonplace. The geographic references mentioned in the following records seem ordinary but they are invested with a lot of meaning for the listener, who can vividly see and acutely hear the images and sounds conjured from the simple references.

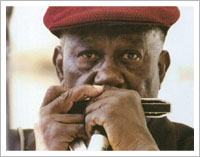

Snooky and Moody’s Boogie/Snooky Pryor and Moody Jones

This downhome blues number from 1949 swings with verve, and Snooky Pryor with his piercingly sharp harp sound blows with elan. Guitarist Moody Jones strums with a robust boogie beat. The number is mostly instrumental, but Pryor talks the lyrics in places, opening with an evocative reference to his neighborhood:

One day

I was walking down Sedgwick Street

I heard a boogie right ’round the corner

Boys, it took me off my feet

And I had to boogie, too.

At 941 N. Sedgwick, Chester and Clara Scales operated the Northside Playland and Record Shop, and owned the Planet label that released “Boogie.” The shop was right in the midst of a small African-American community, at the intersection of Sedgwick and Division, with several blues clubs nearby, notably the Square Deal at 230 W. Division. Snooky and Moody, as did many transplanted southerners, were not yet union members and played on the street instead of in the clubs. “Boogie” could have been about them.

When interviewed by Blues Unlimited in 1980, Pryor said it was Scales who discovered him on the Near North Side – first while playing outside his store with a guitarist named Grey Haired Bill (Johnson), and then playing with Moody Jones and Floyd Jones in a nearby club on Sedgwick.

When interviewed by Blues Unlimited in 1980, Pryor said it was Scales who discovered him on the Near North Side – first while playing outside his store with a guitarist named Grey Haired Bill (Johnson), and then playing with Moody Jones and Floyd Jones in a nearby club on Sedgwick.

James Edward “Snooky” Pryor was born on Sept. 15, 1921, in Lambert, Miss. He got the idea of amplifying his harmonica while serving in the military during World War II, and in 1945 began performing at the Maxwell Street Market with a portable PA system he purchased at a store at 504 S. State St. As the first to amplify a harmonica, Pryor should rightly be recognized as a blues pioneer. As he boasted to Living Blues, “I started the big noise around Chicago.”

Indeed, he makes a plausible claim. “Boogie” represents one of the earliest sounds of the postwar Chicago blues explosion, in which rural southern bluesmen electrified their country blues and created a whole new blues dynamic that helped give birth to rock ‘n’ roll. Among Snooky’s postwar Chicago cohort were Little Walter, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Elmore James, Jimmy Reed and Bo Diddley, and in one small way, this rich blues heritage began on Sedgwick Street.

Hitch Hike/Marvin Gaye

This early Marvin Gaye song on Tamla Records, a Motown imprint, was a nationwide hit in the winter of 1963. The first verse takes Marvin to Chicago:

I’m going to Chicago, that’s the last place my baby stayed

I’m packing up my bags, going to leave this old town right away

I got to find that girl, if I have to hitch hike round the world

Chicago city limits, that’s what the street sign on the highway read

I’m going to keep moving, until I get to that street called 63rd

The song was written in the Motown hit factory, so we can assume that the song’s character began his trek in Detroit and that heading west to Chicago would be his next move. But what is the significance of the street, 63rd?

Back in 1963, when this record was released, probably a large percentage of the African-American listening audience would recognize instantly the significance of the reference. Sixty-Third Street, especially at the intersection of Cottage Grove, was the center of black night life in Chicago. Chicago throughout its history has had several notable black entertainment districts – they were called “strolls” then – beginning with 31st & State in the 1920s, and then moving south to 47th Street & Garfield Boulevard (55th Street) during the 1930s and 1940s, and then to 63rd Street in Woodlawn.

Sixty-Third Street was bisected by Cottage Grove Avenue, and for a couple of decades it was the dividing line between the black and white sections of Woodlawn. The black nightclubs first arose on the west side of Cottage Grove, south and north of 63rd, and then a string went from Cottage Grove along 63rd west to South Parkway (now King Drive). When the color line of Woodlawn broke in 1951, black nightclubs then blossomed on the east side of Cottage Grove and east on 63rd to Stony Island Ave.

One of the most famous clubs on 63rd Street was the Kitty Kat, established in 1953, and which featured King Fleming, John Young, Ahmad Jamal and other more art-oriented jazz musicians. On the west side of Cottage Grove could be found another legendary jazz club, Basin Street, with such stellar acts as Johnny Griffin and Eddie Vinson, and about a block south at 64th Street was the Pershing Hotel complex of venues – the ballroom, the first-floor lounge and the basement club called Budland, which at first was a jazz club featuring such acts as Arnett Cobb, Miles Davis, and Billie Holiday, but later was booking rhythm and blues acts.

On the west side of the Cottage Grove was the Trianon Ballroom, where teenagers saw huge rhythm and blues stage shows, and McKie’s Lounge, which booked a host of great sax blowers. Further east on 63rd Street was the famed Crown Propeller Lounge, which booked both jazz and rhythm and blues acts. The 63rd-Cottage Grove intersection was anchored by the largest theater on the South Side, the Tivoli, which put on rhythm and blues shows as well.

The 63rd Street Stroll also emerged as the South Side’s new “sin strip” during this period. The attraction of the area was “the forbidden,” where one could find not only jazz and rhythm and blues, but smoking, drinking, dope dealing and women. The area attracted not only ardent music fans, both black and white, but also those on the lookout for “action.” The newspapers of the day would periodically send reporters down to 63rd to expose the prostitution going on there. Listeners of “Hitch Hike” in 1963 certainly understood that ol’ Marv was going to a street filled with excitement.

(Native Girl) Elephant Walk/Donald & the Delighters

Vocal groups have always been a huge part of R&B, and Chicago was producing more than its share. Among them, released in 1963, was this incredible record, “Elephant Walk.” The echo-enhanced haunting vocals by lead Donald Jenkins; superb chorusing by his singing mates, Ronald Strong, Walter Granger, and William Taylor; the clashing cymbals; plus the addition of jungle sound effects, all added up to a song atmospherically evocative of its subject. Composer Jenkins tells of a dream by a South Side boy of a native girl in Africa doing a seductive dance called the Elephant Walk. The second verse begins, thusly:

And woh woh, the swaying hips, they put me in a trance

Ummmh, and all at once, I began to dance

The feeling, yeah yeah, yeah yeah, is paradise I know

For an American boy, from the South Side of Chicago

Elephant Walk, ooooh, lord lord, lordy Lord

Crazy memories, lord lord, lordy Lord.

The record was strictly an R&B hit, and was virtually unknown in the crossover pop market, including Chicago. Top 40 powerhouse WLS never played it. The record was not a hit nationwide across all markets, but it sold solidly in some areas, notably Chicago, Pittsburgh and Baltimore. The record has since become a standard in several locales. In the Mexican-American community in Los Angeles, it is considered a low-rider classic, and in Pittsburgh the record crossed over into the pop market and has become a Pittsburgh golden oldie. And of course, in Chicago the record has been continuously played as an oldie now for more than 40 years, particularly on Herb Kent’s weekend dusties show on WVAZ.

Donald Jenkins, the writer of the song, began singing doowops in the hallways on 47th Street in 1955. This was an era when doowop groups would stake out their neighborhoods and would compete in song battles with their wonderful street vocal creations. “Elephant Walk” comes out of that tradition. Jenkins was indeed an American boy from the South Side of Chicago, and he was one of the city’s standout representatives in the creation of an original American folk art form: doowop.

Southside Chicago/Otis Brown & the Delights

In 1966, “Southside Chicago” from Ole Records got good play on WVON, Chicago’s premier radio outlet for black listeners in the city during the heyday of soul music. With its gentle lope, the young Otis Brown sings his verses bragging that he is from the South Side of Chicago over a persistent chorus chanting throughout the record, “South Side Chicago.” The second verse begins:

When you, you wanna to go to a swinging place

The Southside Chicago, girl, you know it’s the place

I can hear it in the morning, yeah

I can hear it in the evening, yeah

I can hear it all the time, yeah yeah, yeah

What he was hearing on the South Side was the city in song, and Brown and his ad hoc group the Delights are so delighted about coming from there they sing “South Side Chicago” some 38 times through the record. While the South Side was in decline at this point, there were still a lot of entertainment venues that kept the African American community vital in 1966. The legendary Regal Theater, at 47th and South Parkway (now King Drive) was still putting on monthly soul shows (where you could see six to nine acts singing all the latest soul hits for a buck-fifty), and such nightclubs as the Sutherland on 47th, Algiers on 69th and the Bonanza around 77th and Halsted were also active. In these showcases, soul music fans could see many of the same acts they heard on WVON, such as Otis Brown.

Olé Records was owned by King Bevill and operated out of his home at 9734 Princeton on the South Side, one of the innumerable small mom-and-pop record labels that helped put Chicago on the map as a soul music center. Bevill and Brown, who experienced the South Side during the latter stages of its glory years, created a fitting paean to the section of the city they so loved.

*

Robert Pruter is the author of such books as Chicago Soul and Doowop: The Chicago Scene. He can be reached at pruterro@lewisu.edu.

*

Comments? Submissions? Send them to Don Jacobson on the Beachwood’s music desk.

Posted on August 13, 2007