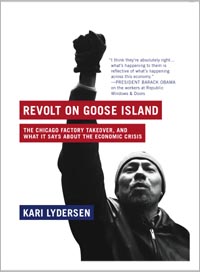

The second of a two-part excerpt from Revolt on Goose Island: The Chicago Factory Takeover and What It Says About the Economic Crisis. Published by Melville House.

Part One: It was like they were mocking us.

By Kari Lyderson

The workers organized a surveillance team that would keep watch outside the factory after hours and on weekends, when the plant was closed. One Saturday, Robles and Revuelta were lurking in the parking lot north of the factory, Robles with his wife Patricia and their young son Oscar in tow. They could see the plant’s front entrance on Hickory Street, where boxes were being loaded onto two trailer trucks. They hopped into their cars: Revuelta drove out after the first trailer, and Robles followed the second one. He wasn’t frightened or intimidated, only determined to see what the company was up to. The union’s contract covers any activity within a 40-mile radius of the plant, and rumors were circulating that the equipment was being moved to Joliet, an industrial town exactly 40 miles outside Chicago.

The two men took note of the trucks’ license plates and followed them for about 15 miles to a truckyard on the southwest side of the city, an industrial, grimy swath of land next to the highway. They parked just outside the yard and, keeping their eyes on the now-stationary trailers, Robles called international union representative Mark Meinster, a 35-year-old Philadelphia native who had been an activist since high school. After studying history at a small college in Pennsylvania, Meinster worked for the national community organizing group ACORN in Washington D.C. But he became convinced organized labor was the best realm to press for larger social change, and in 2002 he moved to Chicago to work for the UE as an international rep, responsible for collective bargaining and worker education in Illinois and Wisconsin.

The two men took note of the trucks’ license plates and followed them for about 15 miles to a truckyard on the southwest side of the city, an industrial, grimy swath of land next to the highway. They parked just outside the yard and, keeping their eyes on the now-stationary trailers, Robles called international union representative Mark Meinster, a 35-year-old Philadelphia native who had been an activist since high school. After studying history at a small college in Pennsylvania, Meinster worked for the national community organizing group ACORN in Washington D.C. But he became convinced organized labor was the best realm to press for larger social change, and in 2002 he moved to Chicago to work for the UE as an international rep, responsible for collective bargaining and worker education in Illinois and Wisconsin.

Meinster asked Robles if they could hold tight for an hour. Robles wasn’t planning to go anywhere. By the time Meinster arrived it was getting dark and cold. They sat inside the car for almost four hours mulling over what they should do. Robles was mad. He has a bright smile and is quick to laugh, but when he senses injustice or unfairness he is equally quick to anger and has no qualms about speaking his mind. That’s one of the reasons his co-workers had voted him president of the union local a year and a half earlier.

“I have a friend who drives trailer trucks. We could steal the trailers, then they would have to negotiate with us,” Robles suggested to Meinster. “Or we could deflate the tires.” The union rep appreciated Robles’ fearlessness but talked him out of his schemes. They hit upon another idea, one with a long and glorious history in union lore: they could occupy the plant. Robles immediately liked the idea. In other countries, including his native Mexico, factory occupations are fairly common. But in the United States the tactic had not been used other than in a few scattered cases since organized labor’s heyday in the 1930s, when auto workers brought the industry’s top companies to their knees with sit-down strikes. Occupying the factory would likely mean that people would be arrested, Robles realized, and there was no guarantee it would work or even gain popular support. But these were economic times unlike any in the past 30 years, and drastic times call for drastic measures.

Over the following days, Meinster and Robles bounced the occupation idea off other workers, and they quickly found six people ready and willing to risk arrest and occupy the plant in the case of a closing or mass layoff. Some workers were not citizens, on probation for minor criminal offenses, or had no one to take care of their children, so they couldn’t risk it. But most everyone who heard about the idea was enthusiastic and vowed to be outside picketing if a takeover started. “I said, ‘Let’s do it!’ We had to do something to get some respect,” said Revuelta. “We don’t know why some bosses just treat the workers like nothing, but we can’t let them do that.”

Meinster was aware the Canadian Auto Workers union had in recent years undertaken several dramatic factory occupations or blockades. In July 2008, an auto parts factory near Toronto closed abruptly; workers only learned about the shutdown from news reports, and they received no severance pay. “We were just thrown out on the street to go straight to the garbage bin,” a machine operator told the media. The company, Progressive Moulded Products, had closed a dozen plants, axing more than 2,000 jobs. Workers blockaded the entrances, preventing Ford, Chrysler, and GM from removing equipment, as the auto giants had been doing at a number of recently shuttered Canadian parts plants. As in the United States, the workers would have been last in line for pay as the company went into bankruptcy. Though these workers were non-union, the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) supported their blockade. The previous year, union Canadian auto workers had occupied a parts plant that had closed in Scarborough and prevented the removal of equipment. That occupation ended victoriously, as the major U.S. automakers who bought their parts from the company put up several million dollars for the severance pay mandated in the Canadian workers’ contracts.

Meinster had never undertaken anything like this before, so he began to do his homework. He made a few calls to his Canadian counterparts to visualize the nuts and bolts of occupying a factory. This included logistics – how to get food into the plant, how to bail people out in case of arrests – and strategy. What would their demands be? Who would be their target?

Over the next few weeks, the workers kept making windows and doors at the factory, but the uncertainty and tensions heightened each day. Plant operations manager Tim Widner told workers he was quitting to become a fifth grade teacher in Ohio. Workers didn’t buy it for a second; they figured he must be going to the same place as all their machinery. “When he said that was when we really knew they were lying through their teeth,” said Meinster. The situation was obviously coming to a head. Over Thanksgiving weekend, the plant would be closed for four days. The union organized four-hour surveillance shifts to run around the clock. Most of the workers were looking forward to big family get-togethers over the holidays, but the situation at the factory cast a pall over everything. It’s hard to look forward to Christmas when you’re afraid you won’t have a job.

Posted on July 31, 2009