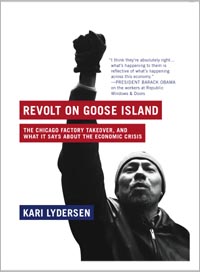

The first of a two-part excerpt from Revolt on Goose Island: The Chicago Factory Takeover and What It Says About the Economic Crisis. Published by Melville House.

By Kari Lyderson

“Turn out all the lights right now,” a supervisor at Republic Windows & Doors told Armando Robles as he was wrapping up the second shift at the factory on Goose Island, a small hive of industry sitting in the middle of the Chicago River. It was about 10 p.m. on November 5, 2008. Robles thought the order strange, as other employees were still finishing up. “Everyone has to leave right now,” the supervisor said. For a while Robles and other workers had been suspicious about the health of the company and strange occurrences at the factory. They knew business had been bad for the past two years. The housing crash meant not many people were in the market for new windows and doors, neither Republic’s higher end ornate grooved, wood-framed glass panes nor their utilitarian vinyl- and aluminum-framed windows. At monthly “town hall meetings” that the company had started holding over the past year, managers were constantly bemoaning how much money they were losing. And the workforce had been nearly cut in half in the past few years, from about 500 to 250. Something seemed to be up, and Robles felt sure it wasn’t good.

He alerted fellow worker Sergio Revuelta, a union steward with eight years at the company. The two left the building as if nothing was amiss, then huddled outside the plant. They watched as the plant manager and a former manager came out and looked around carefully. Five cars drove up. That was strange. “It was all faces and cars we recognized, former employees and former supervisors,” said Revuelta later. Robles and Revuelta watched as the men began removing boxes and pieces of machinery from the low-slung, inconspicuous warehouse. They crept around to the back, where they saw a U-Haul truck waiting with its lights off. Over the next few hours, they watched a parade of objects being loaded into the truck. They were shivering by this time, as they had been sitting in Revuelta’s car, and he had sold the car’s ailing heater to a junkyard. The only illumination came from the light on a forklift. They stayed all night; it wasn’t until almost 5 a.m. that they finally headed home to their families. “We knew something was going to happen, we wanted to watch and see if we were right,” remembered Revuelta, 36.”When we saw the stuff coming out, I said, ‘Bingo!'”

He alerted fellow worker Sergio Revuelta, a union steward with eight years at the company. The two left the building as if nothing was amiss, then huddled outside the plant. They watched as the plant manager and a former manager came out and looked around carefully. Five cars drove up. That was strange. “It was all faces and cars we recognized, former employees and former supervisors,” said Revuelta later. Robles and Revuelta watched as the men began removing boxes and pieces of machinery from the low-slung, inconspicuous warehouse. They crept around to the back, where they saw a U-Haul truck waiting with its lights off. Over the next few hours, they watched a parade of objects being loaded into the truck. They were shivering by this time, as they had been sitting in Revuelta’s car, and he had sold the car’s ailing heater to a junkyard. The only illumination came from the light on a forklift. They stayed all night; it wasn’t until almost 5 a.m. that they finally headed home to their families. “We knew something was going to happen, we wanted to watch and see if we were right,” remembered Revuelta, 36.”When we saw the stuff coming out, I said, ‘Bingo!'”

Revuelta was among the many workers who suspected that Republic management was trying to move their operation elsewhere and deprive them of their jobs. It was a highly disturbing thought. Most of the Republic employees had been there for 10 years or more. The most senior employee had 34 years at the plant. And almost three-quarters of them had come to the United States from Mexico, leaving families and homes behind. Some might have paid thousands of dollars to “coyotes” to lead them across the border, may have walked for days through the stifling heat of the desert, trudging through a seemingly endless landscape of barren, rocky hills and deep arroyos where feet sunk into the soft crumbly dirt. Thousands of Mexicans every year spend this money and take this risk – an average of more than one person per day dies crossing the border – in hopes of getting jobs like those at Republic, earning decent enough wages to bring their families to the United States and also send money to relatives back in Mexico. Many immigrants work at temporary jobs, waiting on street corners on blazing summer days or in the freezing winter to be picked up for construction or transient factory work. Those who land steady union jobs like the ones at Republic, with health benefits and paid vacations, would not give them up easily.

The news of the suspicious night quickly spread to other workers. Robles’ friend Melvin “Ricky” Maclin later heard a similar story from a distraught secretary who said most of the office furniture had been removed. “There was nowhere for them to sit, all the tables, chairs, computers, and file cabinets were gone,” remembers Maclin. He laughed at the bizarre predicament described by the office worker faced with an empty office, but the woman told him it wasn’t funny. The atmosphere had become so tense and strange at the factory that the clerical staff were afraid to speak up, and as they weren’t in the union like the shop-floor workers, they felt they had no one to speak up for them. In the following days, Robles and other workers were ordered to load heavy machinery from the factory onto semi-truck trailers. Sometimes, they were first told to replace components on the machinery with new ones. They saw deliveries being unloaded at Republic that weren’t intended for their plant. One time, a brand-new and mysterious piece of machinery was dropped off after a plant engineer’s mother said it could not be stored in her garage, Robles remembers. The workers knew this equipment wasn’t going to be used at Republic, so what was the company up to?

When they asked managers what was going on, they got vague answers about the machinery being sold to raise money or being sent away for repairs. On Monday, November 17, a whole team of workers who normally made the “Allure” line of windows arrived with no jobs to do, since the machines they usually worked on were gone. Union representatives started filing written requests for information; under their collective bargaining agreement with the company, the union had the right to be advised of major operating decisions or changes. The workers were represented by Local 1110 of the United Electrical Radio and Machine Workers of America, or UE, a scrappy, progressive union with a storied activist history. But they got no response. Workers got more and more suspicious and angry.

“I asked my supervisor, ‘How can I work when I don’t even know if you can pay me?'”said Rocio Perez, a single mother of five and union steward. She felt like the managers viewed them as gullible and naive since they expected them to keep working as the factory was obviously being dismantled under their noses. “It was like they were mocking us.”

–

Tomorrow: An audacious idea takes hold.

Posted on July 30, 2009