By Roger Wallenstein

A little more than two weeks ago my phone rang with a 602 area code on the caller ID, which I recognized as Phoenix. But the number was unfamiliar. After ascertaining that this wasn’t a solicitation or wrong number, the caller said, “I hear you know a lot of White Sox trivia.”

Being a humble and modest fellow who’s been watching the Sox for more than 60 years, I ventured that I knew a few things about the franchise.

“Well, if you know so much, who was the Sox batboy in 1972?” the caller blurted. I countered that I knew the 1954 batboy for the Cubs since he was my future brother-in-law, but, no, I was stumped. “No clue,” I said.

“Well, you’re talking to him,” was the response.

Turns out that Rory J. Clark, who indeed handled the batboy duties for the ’72 team that was honored Sunday at the Cell, shares a mutual friend with me who slyly suggested to Rory that he make the call. I’m glad he did.

Rory and his 21-year-old son Elliott traveled from Arizona to be part of the weekend celebration, which will culminate Monday night with a dinner at the Stadium Club.

Unmistakably, Clark had impressive people skills at an early age, so I wasn’t surprised to learn that for the past 25 years he’s had his own consulting company, Impact Corporation. He has developed a month-long curriculum that teaches sales people every aspect of customer development.

Before yesterday’s nail-biting 1-0 extra-inning win over the Brewers, Rory kibitzed on the field with former Sox Dick Allen, Bill Melton, Goose Gossage, Bart Johnson, general manager Roland Hemond, and others. Just two seasons removed from the 56-106 disaster of 1970, when attendance dipped to 495,000, the ’72 crew went 87-67 and injected new energy and interest into the team, which had been rumored to be headed to St. Petersburg.

Much of the attention on Sunday centered on Dick Allen, now 70, who arguably had the finest season in Sox history in ’72. Clubbing 37 homers, driving in 113 runs, batting .308, and leading the league in seven offensive categories, Allen easily garnered the 1972 MVP award, doubling the total votes for runner-up Joe Rudi.

Yet controversy followed Allen for much of his 15 seasons, including 1974 when he abruptly walked away from the Sox with two weeks remaining on the schedule. He became known as a typically spoiled athlete with a wealth of talent whose ego got the best of him.

Not everyone felt this way since Allen was not an uncomplicated individual, but I can’t recall him ever answering his critics in the press or publicly.

Forty years heals many wounds, and Allen was beaming on Sunday when he threw a perfect first-pitch strike before a cheering and appreciative crowd.

* * *

Going back to that season of long ago, Allen took a liking to the then 17-year-old Clark, who was headed to Northwestern University that fall after graduating from St. Ignatius. They talked often, sometimes in the on-deck circle before Allen performed feats like hitting a 445-foot home run into the old Comiskey Park center-field bleachers or slugging towering shots onto the left field roof.

“One of our conversations involved some criticism he got for how he ran the bases because he didn’t appear to hustle,” Clark told me after Sunday’s game. “After the criticism we were in the on-deck circle and I said, ‘Hey Dick, you got a lot of criticism for not running real hard, and that last double you hit would be an example.

“He said, ‘Rory, that was a double.’ And I said, ‘What do you mean?’ He said, ‘If it had been a triple, I would have gotten a triple. It was a double.’ I said, ‘I don’t know what you mean.’ He said, ‘When I hit it, I knew it was a double. So I ran double speed.’

“A lot of guys would say that and be joking, but he absolutely meant it. He ran the bases with a precision that I have never seen in baseball ever. He touched the corner of the bag, and he ran the shortest route around the bases. He knew baseball inside and out.”

Clark didn’t exactly fall into his job that summer. He aggressively earned it. Living close to Comiskey, Rory previously had jobs such as vending and ushering, so he was known around the place. He described a meeting with Sox general manager Stu Holcomb, who had previously been the athletic director at Northwestern.

“I found out that two batboys were leaving [after the 1971 season], and I saw Stu Holcomb walking through the park one day,” Clark said. “I walked up to him and I said, ‘Hey Stu, you’re going to be losing two batboys next year. I’d like to replace one of them.’ He said, ‘I don’t hire batboys.’ I said, ‘I know you don’t but you run the team, right? So you know who hires batboys, don’t you?’

“I said, ‘So then maybe you could take me down to introduce me to him and then I could get the job.’ He said, ‘Well, why would I do that?’ I said, ‘You were the athletic director at Northwestern, and I’m going there next year so we’re almost brothers.’ He looked at me kind of dumbfounded, and he said, ‘Okay, come and see me when the team’s out of town.’ And then he introduced me to the clubhouse manager and I got the job.”

Hanging out with the likes of Dick Allen might sound like a teenager’s dream, but don’t think that the job wasn’t demanding. Rory arrived at the park three hours prior to game time and remained there three hours after the final pitch.

“Before the game my responsibility was stocking all the food and things we provided for the players, making sure that their lockers were straightened out, making sure the clubhouse was clean, getting their equipment into place,” Clark said.

“We [worked] the game and then after the game we’d have to clean up the locker room, get rid of all the food, and then shine their shoes. We polished their shoes every night. The bane of our existence was when they went to California because California had red clay in the infield so not only did we have to shine the shoes when they came back, but we had to replace the shoestrings because they were all red and nasty. We hated it when they went to the West.”

I’ve always wondered whether ballplayers more or less tone down their conversation when they’re within earshot of the batboys. You know, the role model thing where foul language, talk about off-field escapades and boys-will-be-boys conversation is guarded around kids.

“The locker room is a fraternity,” Clark said. “Everything that happened in the fraternity was known to everybody in the fraternity. I was privy to all of those things. I think that anybody who’s ever been on a sports team would know what I’m talking about.”

Rory tore through a number of other anecdotes about people like pitcher Bart Johnson and Tony Muser, “the two funniest guys on the team.”

But ultimately the conversation came back to the enigmatic Dick Allen. “If you tell only part of the story, then all of a sudden you get the wrong idea about guys, and I think that’s one of the reasons why Dick Allen is not in the Hall of Fame. People have a bad opinion of him for no reason. The guy was private and he was an introvert, but he’s one of the greatest players to ever play the game of baseball. He knew baseball better than anybody.”

–

Together Again: Rory Clark and Dick Allen

–

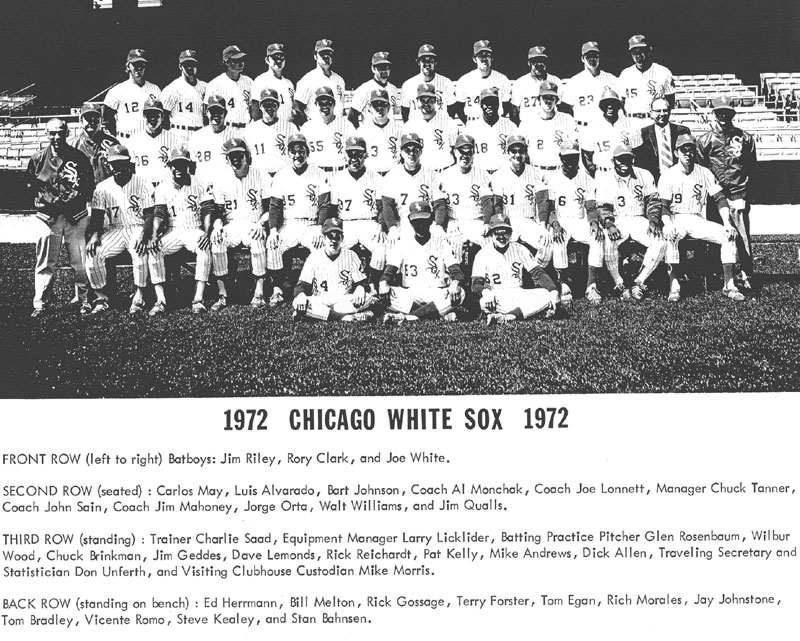

The 1972 White Sox

–

Dick Allen Recalls . . . A Team Tighter Than Pantyhose Two Sizes Too Small

–

Dick Allen Recalls . . . A Team That Had To Be The Blunt End Of A Stick

–

Roger Wallenstein is our man on the White Sox beat. He welcomes your comments.

Posted on June 25, 2012