By Kiljoong Kim

Despite decades of effort – including declaring a war – to alleviate poverty, the struggle to survive day-to-day with low wages and unemployment persists for millions of people.

And though medical advances and the wider availability and lower cost of food have extended the lifespan of even those who struggle financially, this means that many individuals simply live poorly longer, given the lack of economic mobility in our society.

The result is an intersection of poverty with age that shows us not all poor neighborhoods are created equal and, perhaps more importantly, should force us to rethink how we deal with poverty.

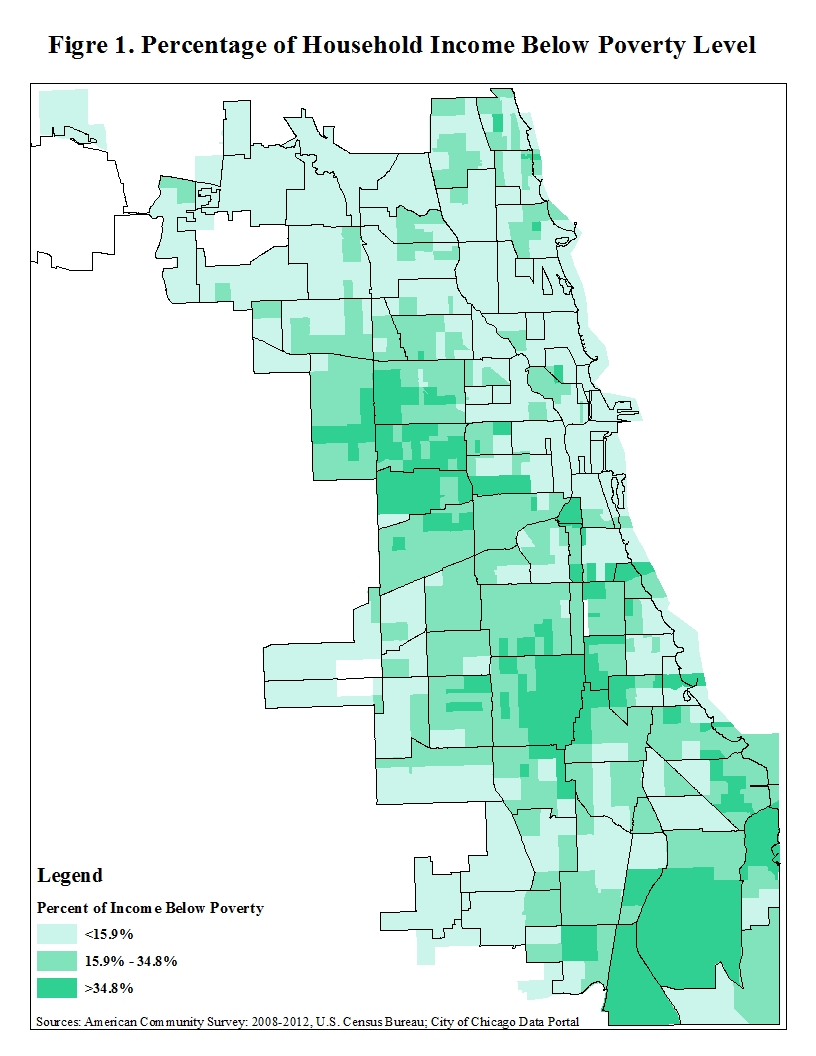

The distribution of households below poverty level in Chicago is not terribly surprising: Most are densely concentrated on the South and West Sides, as they have been for nine decades. The rest are mostly sprinkled in Rogers Park and Uptown on the North Side and South Chicago on the Southeast Side.

(ENLARGE)

(ENLARGE)

While each of these areas are quite poor, the visual landscape between them could not be more different. In Rogers Park and Uptown, poverty takes on the form of densely filled apartments (often architectural mistakes of the 1960s and 1970s), including a rapidly declining number of Single Room Occupancy (SRO) buildings. However, they are also often located a short distance from the lake, public transportation, clinics and soup kitchens.

On the other hand, the impovershed neighborhoods on the South and West Sides feature boarded-up homes, vacant lots and severely limited amenities nearby. The appearance in these areas is far more wretched and isolated than the impoverished pockets on the North Side areas, where the proximity to other amenities and residents of the city presents a type of poverty more integrated into mainstream socioeconomic life.

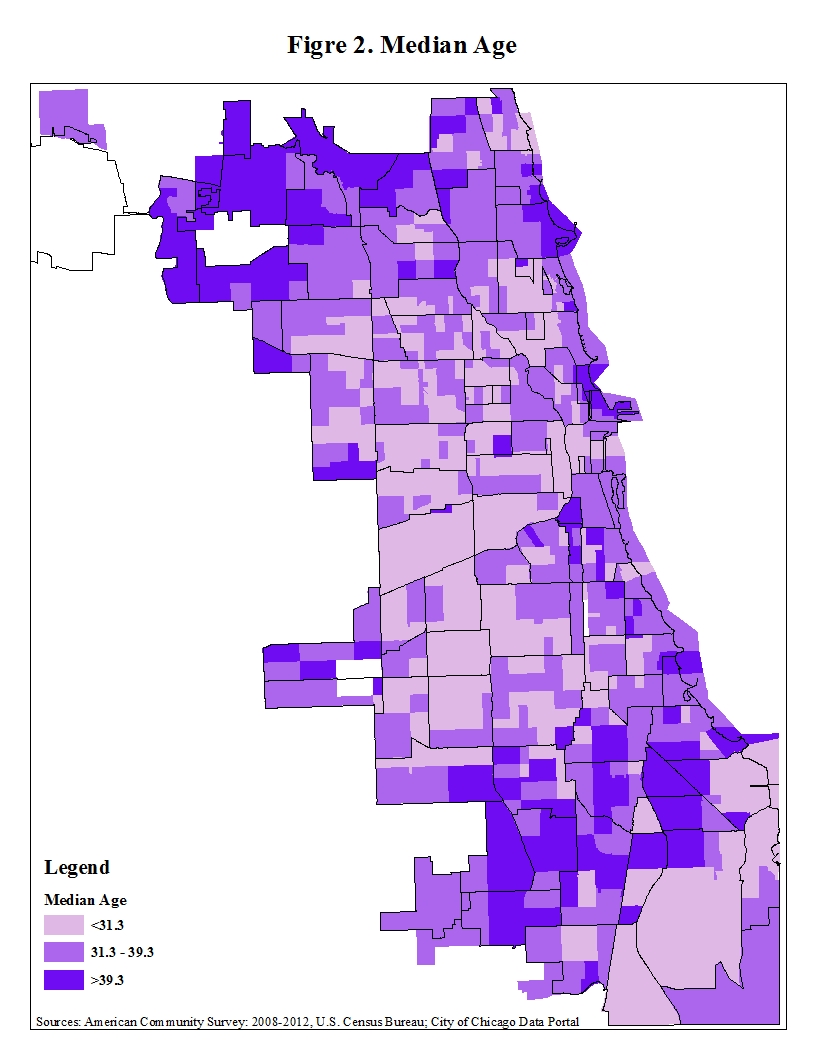

Further, the age differences between these impovershed areas are stark. Median age is a vital gauge for a neighborhood in that it can be one of the best predictor of its longevity. A lower median age often indicates a large proportion of children – and thus a stability to the population, which isn’t likely to change or move any time soon. A higher median age implies a shift in neighborhood composition sooner rather than later as younger people come to supplement a population that is essentially dying off, though it has become increasingly difficult to estimate the timing of such change as individuals live longer.

The days of children of homeowners inheriting the houses of their parents are very much gone, and generational shift often triggers a change in racial/ethnic or economic composition of neighborhoods. The history of Chicago’s ethnic neighborhoods is essentially a history of such generational shifts, going back to the older European (Italian, Irish, Greek, Czech and Polish) and Asian (Japanese and Korean) neighborhoods of previous generations.

According the U.S. Census Bureau, the median age in Chicago is an estimated 33.1, meaning half the population is younger than 33.1 and half is older. Somewhat surprisingly, this measure varies greatly by neighborhood. In one census tract in Garfield Park, the median age is 16.5, which means that a very large proportion of the population there is pre-teen children and teenagers. On the flip side, a Lakeview census tract has a median age of 62.7, which indicates an overwhelming proportion of the population there is near or has reached retirement age.

Overall, the distribution of median age shows that those neighborhoods consisting of an older population are largely located on the peripheral areas of the city for both the North and South Sides: Sauganash, Forest Glen, Norwood Park and Edison Park on the North Side, and Mount Greenwood, Morgan Park, Roseland, Pullman, Avalon Park and Calumet Heights on the South Side.

(ENLARGE)

(ENLARGE)

These areas largely consist of single-family homes dotting a landscape similar to that of middle-class suburbs, and it is not unusual to find government and school administrators living there. There are also small pockets in the Loop, Uptown, Chinatown, Dunning, Lincoln Square and Jackson Park where the median age is substantially higher than that of the city.

Areas featuring younger residents and lower levels of poverty are, unsurprisingly, concentrated in Lakeview, Lincoln Park, Bucktown, and parts of Wicker Park and East Ukrainian Village.

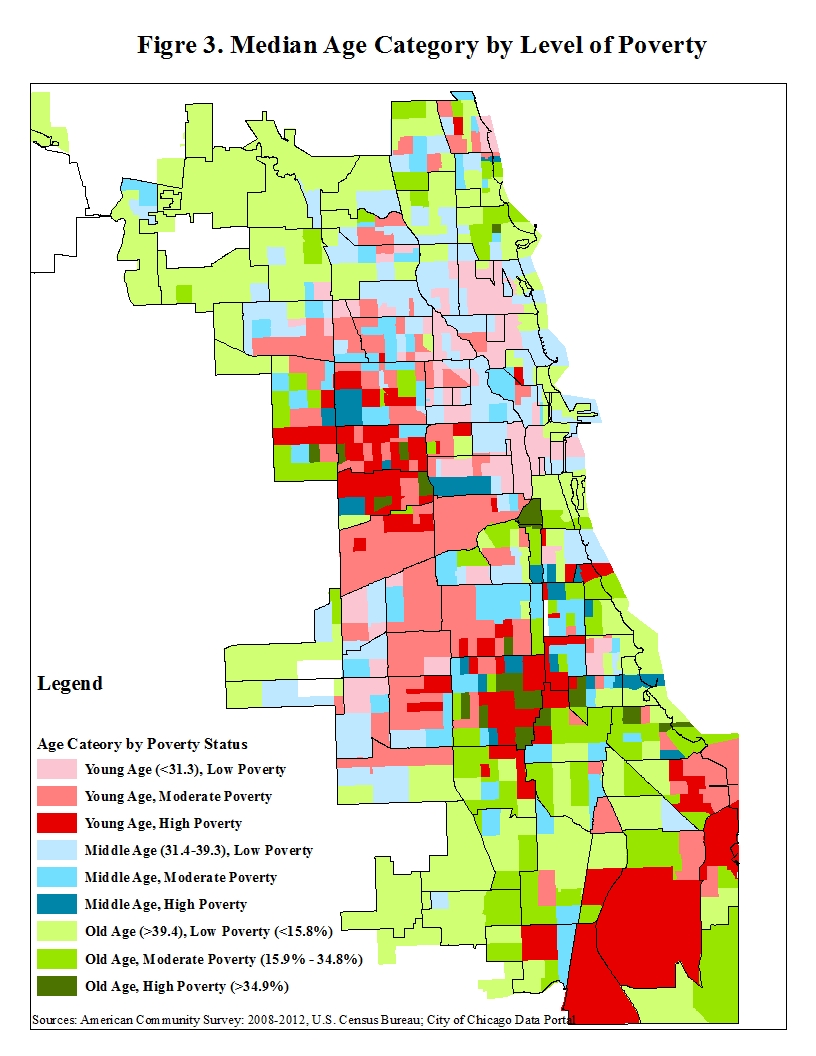

The neighborhoods with older residents and lower levels of poverty are found in Sauganash, Forest Glen and Edison Park on the Northwest Side; Beverly and Mount Greenwood on the Southwest Side; and portions of Hyde Park on the South Side. While these older neighborhoods have been historically known to be stable hubs for upper middle-class residents of the city, much of the aforementioned younger areas had at one point been filled with immigrants and working-class residents until gentrification at varying stages for the past several decades.

(ENLARGE)

(ENLARGE)

The most visible concern with the current pattern is that those areas with high levels of poverty and lower median age tend to be contiguous to one another, creating a large impoverished area consisting of children. Also, older high poverty areas are often surrounded by younger higher poverty areas, creating neighborhoods largely made up of children and senior citizens.

That composition begs the question as to whether impoverished areas like Garfield Park, North Lawndale and Englewood are home for enough wage-earners. If this indeed is the case, economic development in these areas is not likely to come from job creation, as often argued by politicians and policymakers.

Chicago has a painful history of seeing first-hand what it is like to have intensely concentrated poverty. Even after dismantling massive public housing, the city still houses neighborhoods where poor living and economic conditions are the norm. While some neighborhoods turned for the better over time, others remain with conditions comparable to that of many Third World cities. If equity in quality of living is to be a priority for civic leaders, constant monitoring of the shift in population and flexible government structure that can accommodate this shift must be in place.

–

Kiljoong Kim is the Beachwood’s sociologist-in-residence. He recently earned his Ph.D at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He welcomes your comments. Read more in the Who We Are archives.

Posted on October 2, 2014