By Wikipedia

The first person to earn a third term as governor of Ohio, Rutherford B. Hayes reduced the state debt and re-established the Board of Charities. His success immediately elevated him to the top ranks of Republican politicians under consideration for the presidency in 1876.

The Ohio delegation to the 1876 Republican National Convention was united behind him, and Senator John Sherman did all in his power to get Hayes the nomination.

In June 1876, the convention assembled with James G. Blaine of Maine as the favorite. Blaine started with a significant lead in the delegate count, but could not muster a majority. As he failed to gain votes, the delegates looked elsewhere for a nominee and settled on Hayes on the seventh ballot.

The convention selected Representative William A. Wheeler from New York for vice president, a man about whom Hayes had recently asked, “I am ashamed to say: Who is Wheeler?”

The Democratic nominee was Samuel J. Tilden, the governor of New York. Tilden was considered a formidable adversary who, like Hayes, had a reputation for honesty.

In accordance with the custom of the time, the campaign was conducted by surrogates, with Hayes and Tilden remaining in their respective hometowns.

The poor economic conditions made the party in power unpopular and made Hayes suspect he would lose the election.

Both candidates concentrated on the swing states of New York and Indiana, as well as the three southern states – Louisiana, South Carolina and Florida – where Reconstruction Republican governments still barely ruled, amid recurring political violence, including widespread efforts to suppress freedman voting.

The Republicans emphasized the danger of letting Democrats run the nation so soon after southern Democrats had provoked the Civil War and, to a lesser extent, the danger a Democratic administration would pose to the recently won civil rights of southern blacks.

Democrats, for their part, trumpeted Tilden’s record of reform and contrasted it with the corruption of the incumbent Grant administration.

As the returns were tallied on Election Day, it was clear that the race was close: Democrats had carried most of the South, as well as New York, Indiana, Connecticut and New Jersey. In the Northeast, an increasing number of immigrants and their descendants voted Democratic.

Although Tilden won the popular vote and claimed 184 electoral votes, Republican leaders challenged the results and charged Democrats with fraud and voter suppression of blacks (who would otherwise have voted Republican) in Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina.

Republicans realized that if they held the three disputed unredeemed southern states together with some of the western states, they would emerge with an electoral college majority.

On November 11, three days after Election Day, Tilden appeared to have won 184 electoral votes, one short of a majority. Hayes appeared to have 166, with the 19 votes of Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina still in doubt.

Republicans and Democrats each claimed victory in the three latter states, but the results in those states were rendered uncertain because of fraud by both parties.

To further complicate matters, one of the three electors from Oregon (a state Hayes had won) was disqualified, reducing Hayes’s total to 165, and raising the disputed votes to 20.

If Hayes was not awarded all 20 disputed votes, Tilden would be elected president.

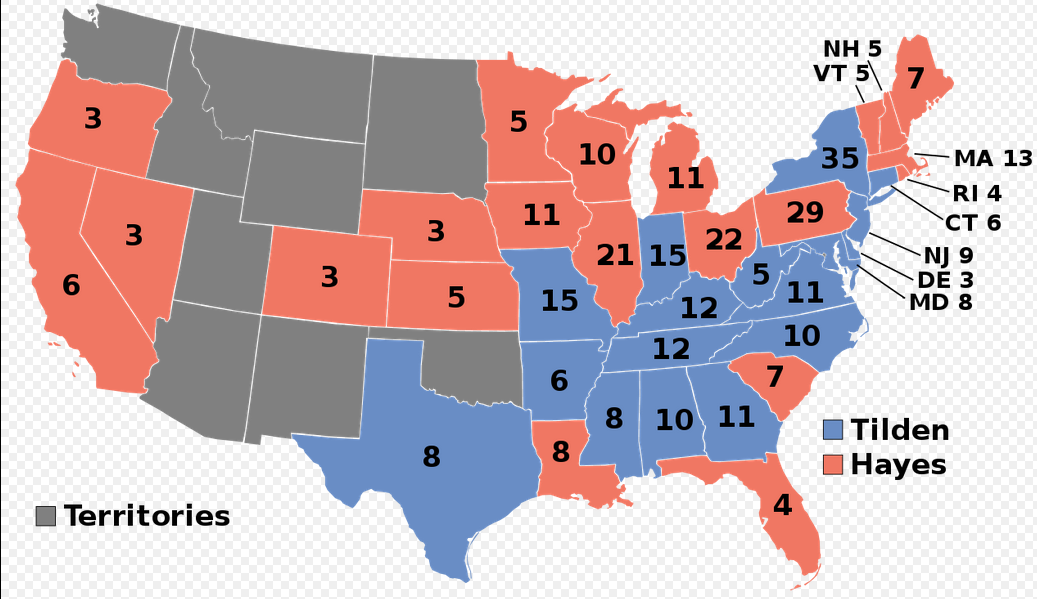

Results of the 1876 election, with states won by Hayes in red and those won by Tilden in blue.

Results of the 1876 election, with states won by Hayes in red and those won by Tilden in blue.

There was considerable debate about which person or house of Congress was authorized to decide between the competing slates of electors, with the Republican Senate and the Democratic House each claiming priority.

By January 1877, with the question still unresolved, Congress and President Grant agreed to submit the matter to a bipartisan Electoral Commission, which would be authorized to determine the fate of the disputed electoral votes.

The Commission was to be made up of five representatives, five senators, and five Supreme Court justices. To ensure partisan balance, there would be seven Democrats and seven Republicans, with Justice David Davis, an independent respected by both parties, as the 15th member.

The balance was upset when Democrats in the Illinois legislature elected Davis to the Senate, hoping to sway his vote. According to one historian, “No one, perhaps not even Davis himself, knew which presidential candidate he preferred.” Democrats in the Illinois Legislature believed that they had purchased Davis’s support by voting for him.

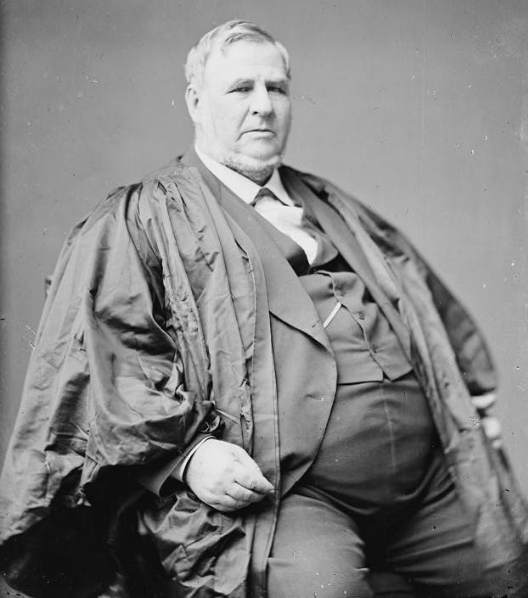

Judge David Davis

Judge David Davis

However, they had made a miscalculation; instead of staying on the Supreme Court so that he could serve on the Commission, he promptly resigned as a justice, in order to take his Senate seat. Because of this, Davis was unable to assume the spot, always intended for him, as one of the Supreme Court’s members of the Commission. His replacement on the Commission was Joseph Philo Bradley, a Republican, thus the Commission ended up with an 8-7 Republican majority. Each of the 20 disputed electoral votes was eventually awarded to Hayes, the Republican, by that same 8-7 majority; Hayes won the election, 185 electoral votes to 184. Had Davis been on the Commission, his would have been the deciding vote, and Tilden would have been elected president if Davis and the commission had awarded him even one electoral vote.

Democrats, outraged by the result, attempted a filibuster to prevent Congress from accepting the Commission’s findings.

As Inauguration Day neared, Republican and Democratic Congressional leaders met at Wormley’s Hotel in Washington to negotiate a compromise. Republicans promised concessions in exchange for Democratic acquiescence to the Committee’s decision. The main concession Hayes promised was the withdrawal of federal troops from the South and an acceptance of the election of Democratic governments in the remaining “unredeemed” southern states. The Democrats agreed, and on March 2, the filibuster was ended. Hayes was elected, but Reconstruction was finished, and freedmen were left at the mercy of white Democrats who did not intend to preserve their rights.

On April 3, Hayes ordered Secretary of War George W. McCrary to withdraw federal troops stationed at the South Carolina State House to their barracks. On April 20, he ordered McCrary to send the federal troops stationed at New Orleans’s St. Louis Hotel to Jackson Barracks.

*

Davis served only a single term as U.S. Senator from Illinois.

In 1881, Davis’s renowned independence was again called upon. Upon the assassination of President James A. Garfield, Vice President Chester Arthur succeeded to the office of president. Per the terms of the Presidential Succession Act of 1792, which was still in effect, the President pro tempore of the Senate would be next in line for the presidency, should it again become vacant at any time in the 3½ years remaining in Garfield’s term. As the Senate was evenly divided between the parties, this posed the risk of deadlock. However, the presence of Davis provided an answer; despite being only a freshman Senator, the Senate elected Davis as President Pro Tempore. Davis was not a candidate for re-election. At the end of his term in 1883, he retired to his home in Bloomington.

Upon his death in 1886, he was interred at Evergreen Cemetery in Bloomington, Illinois. His grave can be found in section G, lot 659.

His home in that city, the David Davis Mansion, is a state historic site. At his death, some believe he was the largest landowner in Illinois, and that his estate was worth between $4 million and $5 million.

His great-grandson was David Davis IV (1906-1978), lawyer and Illinois state senator.

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on November 22, 2020