By Steve Yaccino

Tonight the sky is clear, and a light breeze envelops the street with a chocolate aura. I’m sitting across from the Blommer Chocolate Factory on the Northwest edge of downtown Chicago and I’m 5 years old again, waiting for my grandmother to take cookies from the oven.

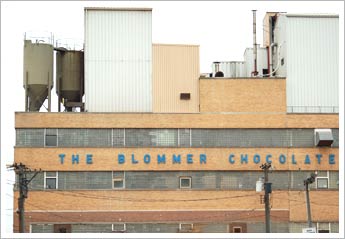

Tonight the factory, at 600 West Kinzie, is awake, glowing in the presence of the city to my back. It breathes in and out, with a soft snort and a sigh, whispering a silent happiness down into my lungs while men, dressed in white, walk to and from their cars. They are wearing plastic shower caps and Mickey Mouse gloves; they resemble a strange crossbreed of scientists, Martha Stewart, and Saturday morning cartoon figures.

For the last two months I have attempted to discover who complained about the chocolate smell that’s now aesthetically paralyzing me. Who, I wanted to know, could be against chocolate?

The complaint triggered an investigation a year ago by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and lead to a citation and “alleged violation” of the 2001 Clean Air Act.

On the surface, it appears the smell has prevailed, that little has changed, that I should sit here content, cologned in this childhood fragrance. But deep in the shadows of looming condos, there is a war that wages between gentrification, government, and cocoa grinders.

The Investigation

The Investigation

In July 2005, a condo dweller who officials still refuse to identify called the EPA complaining of an unpleasant odor coming from the factory. The smell was particularly bothersome when the unidentified complainant used his balcony, he told investigators. At the time, Blommer operated 11 grinders that vented emissions from the northeast corner of the factory roof. The citizen also complained about these visible emissions.

The EPA does not regulate odor. However, on the first and second of September 2005, an EPA inspector found “significant violations” of opacity limitations – for 16 minutes the first day and 10 minutes the next.

Opacity is a subjective measurement that determines the amount of emissions being released into the air. It does so by monitoring how much light is obscured by a plume of smoke, rating them on a scale that ranges from 0 percent (clear smoke) to 100 percent (completely black smoke). Illinois requires factory opacity levels to be at less than 30 percent, with three eight minute exceptions for every 24 hour period. The reading for Blommer ranged from 32.1 percent to 49.4 percent over the two observed days.

Shortly after the testing, Blommer was sent a notice of its violation.

“We were surprised by the allegation,” vice president of operations Rick Blommer wrote in a November 2005 letter sent to neighbors of the factory. “We were in the final stages of adding filter equipment for maintenance purposes that would have the added benefit of decreasing emissions.”

In fact, since 2004, Blommer had been developing a plan to install emission control equipment for its cocoa bean grinders.

“Blommer had told the EPA that they were installing equipment,” says Tom Wolf, a spokesman for Blommer. “There was no fine or payment or agreement that Blommer exceeded the opacity limit.”

Even if there was a violation of opacity limits, the EPA stated in a document obtained by The Beachwood Reporter, “Our complaint did not allege health risk,” and that “No information was found addressing health effects associated with ambient cocoa concentrations.”

“The substance emitted from our plant is organic, not toxic,” Blommer wrote in his letter to neighbors. “The source of the opacity viewed by the USEPA inspector was cocoa butter. Nothing more. Nothing less.”

Blommer installed its emissions control equipment as planned and, according to the EPA, are in compliance with the Clean Air Act today. And it still smells like chocolate.

The Flak

The EPA’s investigation of Blommer was a media sensation, from National Public Radio to 20/20. While the EPA was merely responding to a citizen complaint, the agency caught most of the flak, as pundits opined that “Big Brother” government was ready to take away every ounce of joy and happiness.

“It’s like saying Willy Wonka is a child molester,” says Brian Urbaszewski, director of environmental health programs at the American Lung Association. “I feel bad for the EPA in this situation. They saw a small problem, they addressed it, and fixed it. It’s what they were supposed to do.”

Still, the story blew up. Blommer was news as far away as India and Australia.

I suppose this was the reason the EPA was less than pleasant to work with and gave me a headache on more than one occasion – despite my initial feeling that the real culprit was the guy who filed the complaint.

“All we can say is in the documents I gave you,” USEPA spokesman Bill Omohundro repeated to me several times. These were documents I had already found on the Internet and told me little. He answered very few of my questions, and I had to file a Freedom of Information Act to force the agency to turn over their public records regarding the case.

In the end, however, the agency would not release the name of the complainant, citing a confidentiality policy. The condo owner who started it all is the only one who has escaped scrutiny.

The Air

It wasn’t just the Blommer violation that the media found disconcerting – it was the contrast with the 7,600-plus environmental violations documented by the state attorney general’s office since 1999 that the office says have been ignored by the EPA. Current attorney general Lisa Madigan alleges that six aging coal-fire power plants owned by Midwest Generation, including two in Chicago and three in the suburbs, have been skirting the requirements of the Clean Air Act for decades. And yet, Madigan says, none of the plants has yet received a single citation for these violations.

Madigan sent a scathing letter to the EPA in August 2005 – a month after the condo-owner’s Blommer’s complaint – citing the agency’s “continuing refusal” to address opacity requirements at the power plants, and stating that the EPA “continues to skirt around a clear, absolute, and non-discretionary requirement of federal law.”

A petition was also sent objecting to permits issued to Midwest Generation on the grounds that the factories were out of compliance of their current permits and should be required by law to construct a plan and time frame to reach compliance before new permits go into affect. As of this writing, the attorney general’s office has received no reply to the petition despite the 60-day notice requiring the EPA to respond, according to Ann Alexander, Madigan’s environmental counsel. The deadline for such a response expired more than six months ago and the attorney general’s office is contemplating suing the EPA for a response.

“There are bigger problems that aren’t being addressed,” says Urbaszewski, who called Blommer’s violations “ants” compared to Midwest Generation molehills. “It harms people’s health and robs people of their lives. It’s the 800-pound gorilla sitting behind it that no is addressing that is the problem.”

But the EPA says there is no problem.

“We have continuous emissions monitoring equipment on the power plants and access to all emissions data from them,” says an EPA internal talking points document, obtained by the Reporter, written in preparation for a 20/20 interview.

In an EPA letter titled Draft Response to Public Comments, the EPA writes that the data they are receiving from Midwest Generation is “not determinative of whether these exceedances constitute violations.” They claim that they have taken numerous enforcement actions against power plants, and that comparing Blommer’s situation to coal-fired power plants is not fair because they are vastly different.

But in another document obtained by the Reporter, the EPA does compare the two, saying the particulate matter emissions for all equipment at Blommer “should not exceed a permit limit of 68 tons per year,” and then later stating that a “350 mega watt coal-fired boiler in the Chicagoland area has an average annual emission of 670 tons per year.”

In her letter, Madigan points out the EPA’s disregard for Midwest Generation’s hefty emissions, saying that nowhere in the EPA’s draft response do they deny that opacity violations exist; instead the agency merely argues that the opacities are “too insignificant or too inconvenient to tackle in a compliance plan.”

In 2000, a team of researchers from Harvard University estimated that these Midwest Generation power plants, along with three more elsewhere in Illinois, together cause 300 deaths and 14,000 asthma attacks each year. The report also states that if the plants were forced to follow the Clean Air Act’s pollution standards, two-thirds of those deaths and asthma attacks could be avoided.

The Blommer Chocolate Factory has not been determined to have caused any asthma attacks, much less deaths. The EPA says they don’t overregulate small factories; they merely try to be responsive to citizen complaints, as in the case of Blommer. But they still won’t identify who filed the complaint against Blommer.

The Neighbors

Home to 180 local employees, Blommer has defined its industrial neighborhood for almost 70 years, and has become one of the largest chocolate manufacturers in North America. Like many other parts of the city, though, the area has undergone an extreme form of gentrification, with condos popping up left and right like zits on the face of a post-pubescent teenager. That has put Blommer in the midst of growing neighborhood tension.

Whoever complained about the chocolate smell was neither the first, nor most recent person to do so.

Another complaint was filed with the EPA in November 2005 by a resident who complained of a smell described as “overwhelming, greasy, and not like chocolate at all.”

A third neighbor who complained says the smell has only recently become “unbearable,” and as recent as this last summer, another neighbor complained about unpleasant odor and smoke on his balcony. This neighbor’s long list of frustrations included complaints that Blommer was not maintaining their landscaping and blocking the street with their trucks.

The writing, some might suggest, is on the wall. But many still find the factory endearing and don’t want to lose it.

“People who complain about such things contribute to environmental pollution themselves with their hot air and the wasted paper they use to clog the system,” an irate citizen who works in the area wrote to the EPA. “These are the kinds of people who would move to International Falls, Minnesota, and complain about the cold weather, or would buy a house next to Midway or O’Hare and immediately demand they stop the noise.”

Neighbors Rubin Estremera and Greg Wolk have lived at Kinzie Station, directly across from the factory, for the last five years. “We’ve never known anyone who hasn’t said they love it,” Wolk says. “We were mad when we heard someone complained.”

Out walking their dog recently, the two describe the factory as mysterious and alluring.

“All my friends are envious,” Estremera says. “Who doesn’t want to live next to a chocolate factory?”

Who indeed. That’s the real mystery.

–

Comments welcome.

Posted on November 19, 2006