By Jeff Huebner

Dedicated on September 21, 2006, the life-size bronze sculpture of Charles Gustavus Wicker (1820-89) in his namesake Chicago park depicts the businessman, politician, and developer as an almost forbidding figure. As imagined by sole living descendant, great-granddaughter and sculptor Nancy Deborah Wicker of Harvard, IL, the man who gave the neighborhood its name is shown wearing a grim visage, a Lincoln-like stovepipe hat, and a bulky overcoat that makes him look like a Wild West lawman. All that’s missing is a horse (as if the Park District needs another equestrian statue, anyway).

But our new hero isn’t without props: he’s wielding one of those old round brooms, a reference, as Wicker has said, to how her great-grandfather, despite his social standing, was often seen sweeping the neighborhood and, at least in one instance, an Election Day polling place. Asked why, Wicker allegedly replied, “because it was dirty.” (We take that to mean the floor, not Chicago elections in general.) In other words, the embodiment of the American can-do spirit: “If something needs to be done – do it!”

Yet I can’t help but see that broom as a metaphor. On almost any given day, sitting on tables around the statue, one can find the homeless and the poor who use the park as a shelter and gathering place. Surely, city and park officials as well as many local residents would like to see such elements “swept away” in an effort to make the park as tidy and sanitized as possible for the suburban set and new investment. In some ways, many of these park regulars have become victims to the culmination of a real estate speculation process that began some 138 years ago, when brothers Charles and Joel Wicker helped develop the area, using the green oasis to increase their land’s value.

That’s not all that Wicker’s broom is sweeping away. The installation of this statue in the western portion of the park, between picnic tables and facing east, represents a sanitization of historical memory and place as well. It represents the aesthetic validation and glorification of the Established Political Order at the expense of the community’s labor, working-class, anarchist, and artists’ cultures – a continuum stretching back some 130 years. The park bears scant trace of those historic layers, which have either been erased or remain un-mined.

It is typical in Daley Village that a neighborhood park – a park in a neighborhood as contested as Wicker Park once was, with its storied labor heritage and gentrification struggles – would feature a monument to a developer-politician. It’s all too perfect.

Visiting the park these days – and I am a 23-year denizen – one gets no sense of its (and its surrounding neighborhood’s) role in the Haymarket Affair, in labor and union activities, in the making of a spirited artistic and alternative community that has largely been dispersed to make way for a “post-industrial neo-bohemia” where new bohemians work and play but can no longer afford to live – not to mention Poles, Puerto Ricans, African Americans, and other former residents. (The park does bear a small marker honoring Ignacy Jan Paderewski, the famed Polish composer and statesman who spent a night at 2138 W. Pierce in 1915; yet, contrary to claims, there’s no proof he performed an outdoor concert there.)

Instead, what we get is a traditional, heroic bronze personifying Official History, seemingly sweeping all the other histories away – perhaps because they’re “dirty.” Is this the park’s most fitting memorial? Is this the best symbolic image of the park – and, by extension, the neighborhood – that we want to project to the city and world? (Aside from several temporary art projects, some by children, I’ve never understood why a park in a purported artists’ neighborhood never saw more permanent sculptures by its artists.)

Interestingly, it’s debatable whether the district deserves to be named after Wicker at all: recent evidence suggests it wasn’t his land to begin with, and that it really ought to be called Lee Park. Apparently, Wicker’s clout ensured the endurance of his name.

Charles and Joel settled in Chicago in 1839, opening a wholesale grocery business. Charles went on to own two railroad lines, and to serve as alderman, Cook County supervisor, and state legislator. It’s said he was also an advisor to President Lincoln (which may explain the hat). In 1870, the story goes, the Wickers purchased 80 acres of land along Milwaukee Avenue and staked out various-sized lots (so factory workers, managers, and owners could all live together). The lots surrounded a four-acre park, which the Wickers donated to the city for public use. It just so happened that the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 spurred the first wave of development, and Wicker Park became a fashionable middle- and upper-class district, mostly inhabited by Germans and Scandinavians.

However, longtime resident and historian Elaine Coorens writes in her 2003 book Wicker Park: From 1673 thru 1929 and Walking Tour Guide that it’s not the whole story. Researching title-company tract books, she discovered that the land (including what’s now the park) originally belonged to a D.S. Lee. When Lee died in 1860, the land became the property of his mother Nancy Lee and his wife Mary. When Nancy died in 1868, the so-called Lee Addition was incorporated into the City of Chicago. It was the remarried Mary Stewart who donated the parkland in 1870, which the city transferred to the West Park Commission 15 years later.

Still, the Wickers played a major role in developing the area, since the park bore their name from the beginning. It’s likely they advertised their properties as being close to a park, which would increase their lots’ value. The more things change . . . So: where is the statue of D.S. Lee, or Mary Lee Stewart? Who will commemorate them?

Up until a couple years ago, there was a labor-related memorial in Wicker Park, offering residents and visitors a sense of historical continuum in the neighborhood, one that linked anarchist and working-class movements in the 1880s with anti-gentrification, affordable-housing, and human rights movements more than a century later.

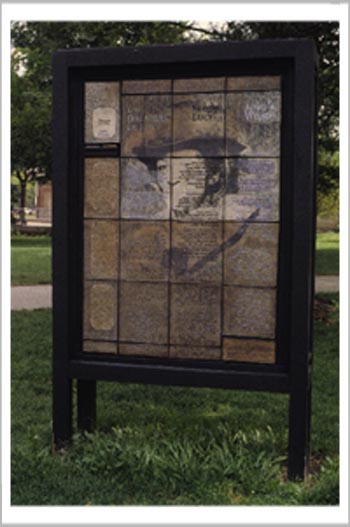

Dedicated in May 1995, the public-art installation Spiral: The Life of Lucy E. Parsons in Chicago, 1873-1942, by neighborhood artist Marjorie Woodruff, was sited in the northwest corner of the park. (Big Disclosure: I met Woodruff while writing a story for the Chicago Reader on her three-year battle with the Park District to install the piece, in 1995. We are now married.) Parsons, of mixed African-American, Mexican, and Native American descent, achieved international acclaim as a labor activist, anarchist, feminist, and author; she was the wife of Albert Parsons, one of the four Haymarket martyrs (of eight convicted) who fought for workers’ rights and the eight-hour work-day, but were executed in 1887.

The artwork was made of wood, metal mesh, boulders, and ceramic tile. It was composed of two pieces – a “conversation box” (in which visitors could deposit written comments) and a spiraling park bench (on which visitors could sit). Both featured text in three languages that highlighted themes in Lucy Parsons’ life and connected them to the present day. At the time, it was the only public artwork in the city’s parks system that commemorated Chicago’s leading role in the nation’s late-19th century labor conflicts – and one of only two that honored a woman. The bench quickly became a gathering place for folks of all kinds, from CHA seniors to brown-baggers to anarchists. (Mary Brogger’s Haymarket Memorial at Randolph and Desplaines – the site of the 1886 protest meeting, bomb throwing, and police riot that resulted in the deaths of seven policemen and four workers – would be dedicated in September 2004.)

Wicker Park played a major role in these events, too. The four Haymarket martyrs – August Spies, George Engel, Adolph Fischer, and Parsons – all lived in the West Town area. After the execution, Lucy and her kids moved near Division and Milwaukee (not far from the Nelson Algren Fountain). On November 13, 1887, the Haymarket martyrs’ funeral procession began at the Spies home, 2132 W. Potomac, and proceeded along Milwaukee, picking up the bodies (which had been returned to their families) on the way. An estimated half-million people lined the street to watch the thousands of marchers.

Further, in his opening address at the Haymarket trial on July 15, 1886, State’s Attorney Julius Grinnell made the egregiously trumped-up charge that Wicker Park – the park – was to be the site for the beginning of the anarchist takeover of Chicago; he claimed they had planned to set a building on fire near there to start the revolution. And, in the days after the riot, police dug up the park – which at that time featured an artificial lake – because they believed bombs had been buried there. None were found.

Visiting the park, few would know these facts anymore. What was Studs Terkel’s phrase – the “United States of Amnesia”? In fact, one doesn’t learn anything about Charles G. Wicker by studying the statue, either. It lacks an explanatory plaque telling us about his life and livelihood, why he’s sweeping the bronze floor with a broom, etc. All that’s there are names and dates on the back of the base. There is no information inside the field house.

Warren Leming, longtime neighborhood resident, writer, and chair of the Nelson Algren Committee, has led tours in Wicker Park highlighting sites associated with the Chicago author as well as with the labor movement and anarchists. Some years ago, he had the idea of installing plaques marking what he calls the neighborhood’s “extraordinary radical background and history, going back to the Haymarket and before.” Leming met with a number of groups to help effect the plan, including the Chicago Historical Society (now the Chicago History Museum). But he says its officials “turned down” the proposal to provide resources for a marker program.

“What is significant is not the history of the bourgeoisie in Wicker Park,” Leming says. “What is significant about Wicker Park is that in the 1880s and 90s there was a thriving working-class culture that was very radical here, which – through attenuation, judicial murder, and other forms of coercion – slowly disintegrated. It was a culture of resistance to the merchant class, which is still in power. Our only historical role is to preserve those whose memory has been carefully forgotten. That’s why we’re doing what we do, because memory is vengeance.” In that sense, he adds, site markers “would be an example to the rest of the world that Chicago has not forgotten the working people who made it. It wasn’t the Palmers, the McCormicks, the Fields, and the rest of them who made Chicago.”

Nevertheless, artist Marj Woodruff (still a West Town resident) won her battle with the Park District to memorialize Lucy Parsons in Wicker Park by the mid-1990s. Spiral, partly paid for by city grants, was intended only to be a two-year installation. But in 1997 the Park District accepted ownership of the piece, including liability costs, with the condition that it would eventually be returned to the artist. Despite her periodic repairs, the work deteriorated. Following Woodruff’s requests (lasting two years), the artwork was finally removed by city workers on May 4, 2004 – coincidentally, the 118th anniversary of the Haymarket Riot.

Perhaps not so coincidentally, the piece was dismantled at a time when the Park District’s proposal to name a planned Northwest Side park after Lucy Ella Gonzalez Parsons was drawing controversy and media attention. The chief critic was Mark Donahue, president of the local Fraternal Order of Police, who protested in a letter to the Park District. On April 15, 2004, he told the Chicago Sun-Times that Parsons “promoted the overthrow of the government and the use of dynamite in getting [her] way.” (The newspaper’s brackets.)

That’s funny. Donahue was a member of the city-convened committee that selected the design for Brogger’s Haymarket Memorial not long before that. He told me in January 2004 that he was honored to be one of two police officials serving on the committee. “We’re part of the labor movement now, too, and glad to be there,” he said.

According to various published accounts, including a January 5, 2006 Chicago Journal article, sculptor Nancy Wicker undertook her own labor-intensive quest to get a statue of her great-grandfather in their namesake plot of ground. She first had the idea in the 1980s, when she was invited to speak at a Wicker Park gathering. But she was hampered by a series of aesthetic and technical setbacks over the years. Wicker secured city and state grants to complete the project, which was eventually approved by the Chicago Park District. From what I was told, the design met little resistance, but the agency misplaced paperwork, delaying installation. (It’s also unclear who “owns” the statue, because it wasn’t a city public-art commission. The artist had to raise funds for maintenance.)

The Park District Board of Commissioners voted in favor of naming a park after Lucy Parsons on May 12, 2004. But nearly five years later, little has been done. The former parking lot at 4712 W. Belmont, at Kilpatrick, remains fenced, weedy, and trash-strewn. The site has only tenuous connections to Parsons’ legacy: While flanked by old factory buildings, it is almost two miles west of her final home at 3130 N. Troy, where she and companion George Markstall died in a fire in 1942. (The house’s location is now under the Kennedy Expressway.)

Until other artists take the initiative to tell Wicker Park’s story with meaningful public art that engages local environment, history, and community, preferably in Charles Wicker’s park, all we’ll have is this bronze figure that’s sweeping, forever sweeping, the past into the dustbin of history. Who will present another vision, an alternate vision, one that’s the metaphorical equivalent of a broomstick being snapped in two over the head?

As Spies proclaimed on the gallows: “There will come a time when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today.” These days, I’m not so sure.

–

Jeff Huebner, a 2005 recipient of the Nelson Algren Community Service Award, is a Chicago-based arts journalist and freelance writer who often writes on public-art projects and issues. He is the co-author of Urban Art Chicago: A Guide to Community Murals, Mosaics, and Sculptures and Chicago Parks Rediscovered: The Photographs of Frank Dina, among other books.

Posted on February 12, 2009