By Roger Wallenstein

Second of a four-part series. Part One is here.

From the day Oasis students first walk in the door, they’re already behind and beginning a lifetime game of catch-up.

“[B]y the time high-income children start school, they have spent about 400 hours more than poor children in literacy activities,” the New York Times reported last month.

For the 698 students at Oasis in grades K-6, that means parents have spent about a half-hour less per night reading to their children before they enter school than parents of means.

Couple that with the fact that English often is not spoken at home. Then consider that just 25 percent of Oasis’s parents have finished high school. Many of these folks spend the day picking strawberries or pruning grape vines. Making dinner and falling into bed just might take precedence over reading to their toddlers at the day’s end.

But Oasis is trying to change that.

“One of the things that we encourage the parents to do is read to them,” says principal Dora Flores. “And to listen to them read. I don’t know how often or what the percentage is. That’s not something I can measure. But I do know it happens. And every time we have a parent night or parent conferences, that is one of the things that the teachers emphasize. We’re moving away from how is my kid behaving in school and those types of questions to educating the parents to ask the right question. It’s not just student behavior, but how can I help my student with the academics.”

* * *

After working for an hour in the classroom, the students have a 20-minute recess. One morning on the playground I noticed my wife Judy walking arm-in-arm with Cecilia, one of our fourth-graders. Later Judy tells me that Cecilia was describing her day, which began at 5 a.m.

“What time do you go to sleep?” Judy asked.

“Eight o’clock,” Cecilia said, explaining that she needs to rise before dawn because dawn is when her parents need to arrive in the fields. An aunt picks up Cecilia and brings her to her house before bringing her to school at 8:30.

Angel is another student with a fervent desire to learn and improve his skills. We were reading a book about fashions through the decades, including a chapter about women in the 1940s who worked at “men’s jobs” while the men were away at war.

Women, it turned out, began to wear pants to work. Angel offered that his mother also wears pants to work. “Oh, and what does she do?” I asked. “Strawberries,” he said. I asked whether she picked them, planted them or pruned them. His answer was vague. I couldn’t tell if he simply didn’t know or didn’t want to say. I asked what his father did. “I don’t have a father,” he said.

* * *

None of this essence and fiber of Oasis’s young people is reflected if you look only at standardized test scores.

“I need to look at the data all the time,” says Flores. “I need to look at how my kids are doing and how they’re scoring. The teachers may tell us that the students are learning, and we can see that the students are learning, but the state tells us what they should be learning and how they’re going to be measured.”

As a school, Oasis tests in the bottom 10 percent of all schools in California. Conversely, the top 14 schools in a place like Palo Alto- where virtually all of the parents are college-educated – are in the top 10 percent. No surprise there.

But Flores isn’t looking for sympathy. Actually, just the opposite.

“For a long time in the district we had the pobrecito syndrome,” she says.

“Oh, poor me, you can’t do that. Or he can’t speak English, that’s okay. Or you come from a poor family. We can’t expect you to learn or do X, Y, and Z because of your demographics or background. It’s all external, and one of the things we tell the teachers is we can’t control what goes on outside the four walls of your classroom.

“But we do have to show [students] respect by our teaching. We have to give them the best quality education we can provide. We cannot control whether the parents read at home with them. We cannot control if they go home to a poor trailer. We cannot control the fact they go home to an empty house. We cannot control six families living together in one trailer. Any of those external circumstances we have no control over. Once they get on that bus and they come to us and they walk into that classroom, then we take control.”

* * *

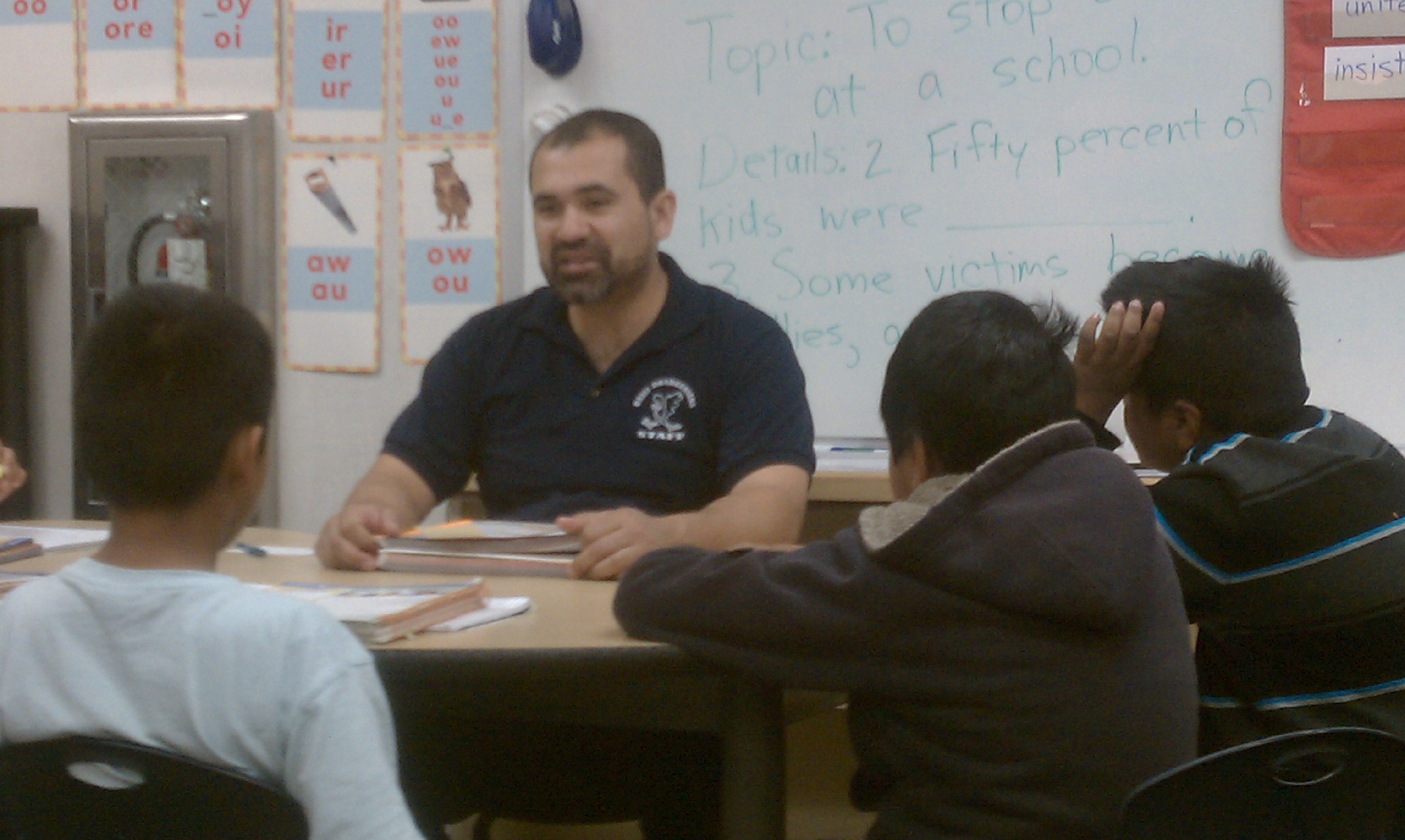

In Ramiro Zamora’s classroom, control never seems to be an issue. I’ve seen 10-year-olds who struggle with transitions going from one activity to another. However, when Mr. Z’s 17 students return to the room from recess, they obediently line up, walk into the class and pick up right where they left off 20 minutes earlier. It’s all business. But don’t assume we have little automatons here who do exactly as they are told. These kids still possess spirit, pizzazz, and individuality.

One December morning when we entered the room, Mr. Zamora was standing in front of his charges, leading a discussion about 9/11. Apparently the class had read a page in its workbook about airport security, which led to the reasons for increased security, i.e., 9/11.

Every kid had his or her eyes on their teacher and seemingly was interested in what he was saying. José and Victoria consistently had their hands up with questions or comments. Toward the end of the discussion, Victoria even stated that she remembered when the planes hit.

“How could you remember that?” asked Zamora. “You weren’t even born yet.”

Some kids might be embarrassed for their exaggeration or embellishment, but Victoria is gutsy and was undaunted. Her teacher let her off the hook by suggesting that maybe she had seen video of the attacks.

* * *

When the kids hear that we’re from Chicago, they have no idea where that is.

If we ask, “What state do you live in?” some even say, “Thermal.”

Their world knowledge is painfully limited, but they’re not afraid of asking questions and making mistakes that lead to enlightenment.

While the raw test scores for the school are low, the state does account for what’s known as adequate yearly progress. For instance, in 2008 just 13.2 percent of Oasis’s students tested as “proficient” in language arts. In 2011 that number jumped to 29.4. In mathematics where language imposes fewer limits, more than half of Oasis students test proficient.

However, there is a cost for testing. Language and math are the focus while music, art, drama and even science and social studies take a back seat or are nonexistent.

“We have to put an end to our obsession with testing, which was supposed to be a way of assessing reform but is now treated as actual reform,” Arianna Huffington writes in Third World America. “It’s as if the powers-that-be all decided that a check-up was as good as a cure. The focus on testing reduces teachers to drill sergeants and effectively eliminates from the school schedule anything not likely to appear on a standardized test – things such as art, music, and class discussions.”

We’ll take a closer look at the effects of testing and the broader educational experience when we return to Oasis Elementary next week.

–

Comments welcome.

–

1. From Cris Rogers:

Enjoyed reading this article, Roger.

I remember when I went for my first time and Judy introduced me and at the time I had just moved from Canada. We discussed where that was, and in fact Mr. Zamora had a projector set up so we were able to google map to where my house was in Edmonton . . . pretty amazing. But, I guess my main point is that in talking about the geography and some tidbits about Canada, I realized how very little the kids really knew or understood about other countries . . . even one that borders the U.S.

Too bad more time can’t be spent on learning more about the bigger picture of the world we live in, outside of California and the U.S. Sometimes those educational experiences can really motivate some kids to reach beyond.

2. From Sally Stein:

Great article, Roger. Just thought it would interest you to hear that we have a friend with a great dog. She brings the dog to a classroom reading hour, and the dog sits up looking like she is listening alertly as the children read to HER. It evidentally is a real motivator for the kids.

And keep up the good work, both of you. You are making a difference, and that is what it is all about.

3. From Eric Davis:

Thank you for your four-part series on Oasis. Your anecdote featuring Cecilia resonated with me. We have several refugee students enrolled at Global Citizenship Experience High School in Chicago. Lele, one of our most promising, goes after learning opportunities with a fervor we WISH all students could demonstrate. But his English language skills are still a work in progress. Standardized Tests present the worst picture of him – and an inaccurate one too. If you want to really know Lele, please view his digital portfolio – gcevoices.com/ln – and this is another trouble. Our school features digital portfolios so that students like Lele, or Oasis’ Cecilia, and all unique individuals for that matter, have an opportunity to showcase their strengths, whether or not they can pronounce the “r” in “run” or tolerate the vocabulary in standardized test reading comprehension sections. But all schools cannot afford this option. So we must find other ways to help our students share their voices, tell their stories, demonstrate their knowledge, and showcase their abilities.

If we don’t, then we fail our students in more than just the fourth-, eighth- or twelfth-grade. We fail them in life because we deny them pathways to pursue their potential.

Posted on March 20, 2012