By Marilyn Ferdinand

Is honesty a virtue? The three films I saw last night at the Chicago International Film Festival hedge their answers, but not necessarily because dishonesty pays. Rather they seem to tell us that truth might be there, or not there, and possibly is irrelevant.

Slumming, from Austrian director Michael Glawogger, presents us with several disagreeable characters. Sebastian (August Diehl) is a bored, idle, rich boy whose time is taken up inventing unflattering stories about the people he sees on the street, slumming in dive bars, and playing cruel practical jokes with the help of his partner-in-crime Alex (Michael Ostrowski). Sebastian meets girls he or Alex find in chat rooms and takes pictures of their crotches with his cell phone while they are sitting having a meal together.

One day, he meets Pia (Pia Hiezegger), a schoolteacher whose friend set her up with him in the chat room. Sebastian falls madly in love with her. Unfortunately, before he realizes this and becomes a better man – isn’t that what’s supposed to happen? – he and Alex kidnap Kallman (Paulus Manker), a schizophrenic poet who they find passed out in a drunken stupor on a park bench across from the Vienna train station. They drive him to the Czech Republic and deposit him on another park bench across from a train station. Alex, who has been pushed past his comfort zone with this prank, nonetheless starts laughing that the guy will think the train station shrunk. His glee is false, however, and he eventually falls silent as Sebastian takes up the joke. Sebastian insists he did Kallman a favor, gave him a clean slate, so to speak.

Kallman isn’t a lovable maniac. He’s abusive and beats a young man senseless to steal his bag of electronic toys to sell in the yuppie cafes. We watch in horror as he downs half a bottle of rum in one swallow, spilling all over the front of his filthy clothes. Nonetheless, he seems so vulnerable when he finds he’s far from Vienna, shivering during a snowstorm inside an unheated shed. But Sebastian was right. Kallman does seem to recapture a certain joy to life during his enforced vacation.

Kallman isn’t a lovable maniac. He’s abusive and beats a young man senseless to steal his bag of electronic toys to sell in the yuppie cafes. We watch in horror as he downs half a bottle of rum in one swallow, spilling all over the front of his filthy clothes. Nonetheless, he seems so vulnerable when he finds he’s far from Vienna, shivering during a snowstorm inside an unheated shed. But Sebastian was right. Kallman does seem to recapture a certain joy to life during his enforced vacation.

Sebastian, too, gets a new lease on life after Pia dumps him because of his cruel joke on Kallman. He travels to Jakarta with one of his chat room dates to try to forget Pia, and hops off the train in a shanty town along the train tracks. Now this is real slumming, but because he is not in his own country, Sebastian can actually see the inhabitants for what they are without contempt. In a humorous scene, two Indonesians start making up a story about him, just as he used to with Alex about the people he observed in Vienna.

Have Sebastian and Kallman reformed? Sebastian may have grown up some, but he’s got a long way to go. And as long as Kallman self-medicates with booze instead of antipsychotics, he really can’t improve. What seems real for each of these two men – an actual slum in Indonesia and contentment – really isn’t. So what does this movie teach us? In my opinion, one thing: Travel broadens a person. I’m afraid that, for me, the unpleasantness of the characters wasn’t worth the payoff.

*

La Terra, an Italian film from director Sergio Rubini, is a comedy about four brothers whose lives are in crisis. Luigi Di Santo (Fabrizio Bentivoglio), a professor living in Milan, travels to his home town of Mesagne in the southern Italian province of Puglia to help approve the sale of the family estate. The hardscrabble 16th century town and the Di Santo feudal estate take Luigi back in time and fill him with both nostalgia and remorse. He has been absent a long time – since he was sent to boarding school as a teen after accidentally killing his father by throwing a glass jug at his head to stop the beating his mother was taking.

La Terra, an Italian film from director Sergio Rubini, is a comedy about four brothers whose lives are in crisis. Luigi Di Santo (Fabrizio Bentivoglio), a professor living in Milan, travels to his home town of Mesagne in the southern Italian province of Puglia to help approve the sale of the family estate. The hardscrabble 16th century town and the Di Santo feudal estate take Luigi back in time and fill him with both nostalgia and remorse. He has been absent a long time – since he was sent to boarding school as a teen after accidentally killing his father by throwing a glass jug at his head to stop the beating his mother was taking.

Luigi’s young brother Mario (Paolo Briguglia) works with handicapped children and adults. His brother Michele (Emilio Solfrizzi) is running for office and lives high on the hog on his wife’s money. His bastard brother Aldo (Massimo Venturiello) lives on and works the family estate, and refuses to sign the papers to sell the land because of bad blood between him and Michele. People are having affairs, suffering heartache, and most of all, owing money to the slimy Tonini, played by the director himself. Luigi becomes embroiled in all the messy affairs of this messy southern town from which he had tried to divorce himself. When a murder is committed, the Di Santos come under intense scrutiny. Luigi must make a choice – himself or his family. He’s Italian. What choice do you think he makes?

A less-than-original moral to the story might have hampered a drama. As a comedy with one of the most effectively silly scores I’ve heard in a while, La Terra allows us to have fun following the twists and turns that tie Luigi in knots and wonder what shady deals and lies he will be willing to make to save his family. Unfortunately, the film is at least 20 minutes too long. It should have crackled with action. Instead, it sets up an intriguing plot point, only to squander its comedic possibilities with digressions and family drama. La Terra was nominated for a slew of Donatello Awards, the Italian version of the Oscars, sadly indicating that the slump in Italian filmmaking continues.

*

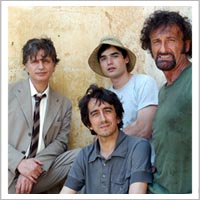

The Romanian comedy 12:08 East of Bucharest (A fost sau n-a fost?) is a superb example of the Balkan humor that makes films from this region of the world so biting and interesting. Director Corneliu Porumboiu takes us to a small city east of Bucharest to capture the state of the art of Romanian society. His film focuses on three men: schoolteacher/drunk/debtor Manescu (Ion Sapdaru), retiree Piscoci (Mircea Andreescu), and entrepreneur/talk show host Virgil Jderescu (Teodor Corban), who eventually discuss whether the revolution that toppled the dictatorship of Nicolae Ceausescu really happened in their town.

The Romanian comedy 12:08 East of Bucharest (A fost sau n-a fost?) is a superb example of the Balkan humor that makes films from this region of the world so biting and interesting. Director Corneliu Porumboiu takes us to a small city east of Bucharest to capture the state of the art of Romanian society. His film focuses on three men: schoolteacher/drunk/debtor Manescu (Ion Sapdaru), retiree Piscoci (Mircea Andreescu), and entrepreneur/talk show host Virgil Jderescu (Teodor Corban), who eventually discuss whether the revolution that toppled the dictatorship of Nicolae Ceausescu really happened in their town.

A slightly offkey clarinet sounds, and the film opens with street lights coming on, block by block, throughout the town at dawn. The lights on the Christmas tree in the square shut off. It is December 22, the 16th anniversary of the Romanian revolution. We first visit Manescu, who stumbles into his living room, passes out on his sofa, and is revived by his wife and warned to bring home his pay envelope immediately after school – or else. Jderescu phones him and asks him to be on his talk show that day. Manescu goes to his bartender for a bottle of liquid courage, but his tab is so high that the bartender initially refuses. Promising the bartender his paycheck, Manescu then has to borrow money to fill his pay envelope for his wife. He gets the money from a Chinese dry goods dealer he has insulted the previous night while drunk, but only by promising never to do it again.

Piscoci is an idle retiree who agrees to play Santa Claus for a friend because he has nothing better to do, then complains about the condition of the costume she provides. He also ends up at the dry goods store, where he buys a new Santa suit and some firecrackers to startle some children in his apartment building who have been lighting them in front of his door and then ringing his bell. Jderescu also asks him to be on the show because he was old enough to be in the square on the day the revolution started, but mainly because his other guest never returned his phone call.

Jderescu is a blustering, self-important philanderer who threatens to fire his lover when she says she’s going to Bucharest for New Year’s instead of being available for him. She ignores him. He sits on the bed with a puzzled and defeated look on his face. Later, he gives his two guests a lift in his broken-down car and is forced to take them to the market before the show to pick up Christmas trees. He’s a boss without a following in true Romanian style.

The meat of this film is the talk show. The three men sit in front of a backdrop depicting the town square. Jderescu says gravely to his audience that the question for the day is whether the revolution came to their town. For him, the answer hinges on whether anyone protested in the square before 12:08 p.m., the time that word of the revolution in the town of Timisoara came through. Manescu insists he was in the square before the crucial time and was beaten by a certain member of the Securitate, Romania’s secret police, who is now a major business owner in town. Several callers say he wasn’t. One woman says he was in a tavern. The former Securitate member calls and threatens a lawsuit if he is accused of these beatings again. His sinister tone is hilarious. Piscoci said he went to the square after 12:08, but what does it matter? It is like the lights in town. They come on at night a few blocks at a time, not all at once. Jderescu disputes this fact and yells at his cameraman to stop being a hotshot and carrying the camera around. “Put it back on the tripod, or I’ll fire you” he blusters. The cameraman ignores him. The three men sit morosely in front of the backdrop until the show whimpers to a close.

Jderescu’s talk show, a cable-access look-alike, is absolutely hilarious. At the same time, there is an underlying seriousness to the proceedings that Romanians must be tuned into – what were you doing when the Revolution happened. The lawsuit-threatening businessman’s previous affiliation with the Securitate – he claims he was just an accountant – reveals a level of distrust and divisiveness still plaguing the country, and one look at the town and the constant haggling about money highlights the country’s economic stagnation.

12:08 East of Bucharest has won numerous awards, including the Camera d’Or at this year’s Cannes Film Festival. It was an honor for me to watch this clever and boisterous continuation of the long conversation that is Balkan cinema.

There is one more showing of Slumming on Wednesday, October 18, at 6:30 p.m. at Landmark’s Century Centre Cinema, 2828 N. Clark. There are no more showings of La Terra or 12:08 East of Bucharest. They may become available on DVD or at one of the cinema art houses in Chicago in the coming months.

Marilyn Ferdinand is The Beachwood Reporter‘s resident film critic, and the proprietor of Ferdy on Films. Her exclusive coverage of the Chicago International Film Festival includes:

* “Better Than Fiction,” her opening guide to the festival.

* “Corruption and Comedy,” a review of The Comedy of Power, a French New Wave film whose themes will be instantly recognizable to anyone with even the sketchiest knowledge of Chicago politics.

* “Soul in Flames,” a review of Requiem, a remarkable film about modern-day possession and exorcism.

* “A Talent for Torment,” three reviews in one (Spirit of the Soul, Ode to Joy, Steel City) from a disappointing day at the festival.

* “Deep in the Heart of Dixie,” a review of Dixie Chicks: Shut Up and Sing, the inside story of the Dixie Chicks’ political and personal journey as Southern girls ashamed of their Texan president.

* “Boot Straps and Black Boys,” a review of Shoot the Messenger, a British film that challenges standard racial notions in part by featuring a character who might best be described as a black Joe Lieberman Republican.

Posted on October 17, 2006