By Connie Nardini

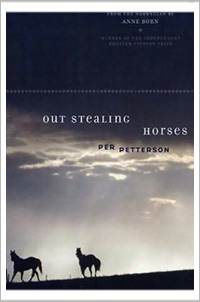

Out Stealing Horses: A Novel

By Per Petterson

–

“Are you coming?” he said. “We’re going out stealing horses.”

Trond and his friend Jon start out on a sunny morning in 1948 for one of their usual summer adventures in a small and isolated farming community in northern Norway, near the border with Sweden. “Stealing” meant going for a wild ride, bareback, on some neighbor’s horses without permission. Petterson takes you with Trond; you leave safe and its twin, sound, and you have landed . . .

“. . . on the horse’s back, a bit too close to his neck, and his shoulder bones

Hit me in the crotch and sent a jet of nausea up into my throat . . . I heard Jon yell ‘Yahoo’ behind me and I felt like yelling too, bit I couldn’t do it, my mouth was so full of sick that I couldn’t breathe . . .

“There was a rushing sound, and the hoof beats died down, and the horse’s back drummed through my body like the beating of my heart, and then there was a sudden silence around me that spread over everything, and through the silence I heard the birds. I distinctly heard the blackbird from the top of a spruce tree, and clear as glass . . .

“There was a rushing sound, and the hoof beats died down, and the horse’s back drummed through my body like the beating of my heart, and then there was a sudden silence around me that spread over everything, and through the silence I heard the birds. I distinctly heard the blackbird from the top of a spruce tree, and clear as glass . . .

“I heard the lark high up and several other birds whose song I did not know, and it was so weird, it was like a film without sound with another sound added, I was in two places at once, and nothing hurt.”

This ride ended at a barbed-wire fence with the result of a very sore Trond.

Again and again Petterson, in this year’s Out Stealing Horses’ English language debut, makes you breathe Trond’s breath and uses his blood for your own. This is a coming-of-age story: A 15-year old and his father spend a summer rural Norway, leaving a mother and a sister in Oslo so they can harvest the timber on the farm the father had bought. The father-and-son relationship seems one that can only be called classically great – one that is strong without being controlling, one that is tender without being cloying. Above all, it seems to be a very nurturing one.

After the horse adventure, Jon behaves very strangely. He abruptly abandons Trond, leaving him aching and very cold to walk home alone. Trond finally arrives at his father’s cabin and this is the sight he sees:

“The sky was darker now than it usually was at night. My father had lit the paraffin lamp in the cabin, there was a warm and yellow light in the windows, and the grey smoke swirled up from the chimney and was immediately beaten down by the wind, and water and smoke ran down the slates on a blend that looked like a grey porridge. What a weird sight . . . ”

What a symbol for the soft enclosure of a warm and safe love.

A modern-day parallel story runs alongside the 1948 scenes. Trond, now 70 years old, has purchased the farm and retired there – a widower with a grown daughter who lives in a distant town. His only companion is his dog, Lyra, whom he takes for daily walks. He meets his nearest neighbor and discovers that the neighbor, Lars, is the brother of Jon – a brother who survived a tragedy that happened to Jon’s family on that long-ago day while he and Jon were “out stealing horses.”

Slowly we learn why Lars is the last person Trond would ever want to see. Slowly Trond’s father (who is never named) is revealed as a man who had a secret life during the war. To him, “out stealing horses” stood for his activity as an undercover agent who smuggled refugees out of Norway and hid them in the very small town where Trond spent the summer helping his father harvest lumber to send downstream to a Swedish mill. Slowly we understand how this summer came to be a turning point in the life of a 15-year-old who wanted, above all, to be like his father.

Petterson uses the rhythm of the work done that summer – haying and logging – to play, like an ancient Gregorian chant, a hymn to nature and to the means of interweaving of a bond between father and son. The apex of the melding comes when Trond and his father follow the cut lumber down the River Glama into Sweden. There they come upon a logjam and Trond leaps onto the pile to find the trouble:

. . . my father called from the bank:

What are you doing out there?

I’m flying! I shouted back.

When did you learn to do that? he shouted.

When you weren’t looking, I called and laughed . . .

When Trond finally loosened the jam, his father says, “Goddamn it, that was not bad.” Praise indeed.

But it takes the retired, modern-day Trond to learn the real lesson of that summer and its aftermath. He saws a large spruce tree, fallen in a storm, and reacquaints himself with the song of labor as his body vibrates with the energy of a chainsaw. His ghost from the past, Lars, helps him even though Trond thinks he doesn’t want to accept the favor because it brings back past anguish.

But Trond finally does accept the last lesson his father taught him: The older man had given him the task of pulling up some nettles that were too close to the cabin. When Trond delays, his father asks him why.

“‘It will hurt,’ I said. Then he looked at me with half a smile and a little shake of his head. ‘You will decide for yourself when it will hurt . . . ‘ He walked over to the nettles and began to pull them up with perfect calm, one after the other, throwing them into a heap, and he did not stop before he had pulled them all up . . . ”

A simple lesson . . . but oh, so hard to learn.

–

Previously in Connie’s Corner:

* “Heavier Than Air.” Nona Caspers creates a tapestry of small towns and chronicles the lives of people living there who have a hard time coming down to earth.

* “Pale Fire.” Nabokov creates a novel that doesn’t seem to have coherent plot but a story that contains a do-it-yourself kit.

Posted on November 26, 2007